|

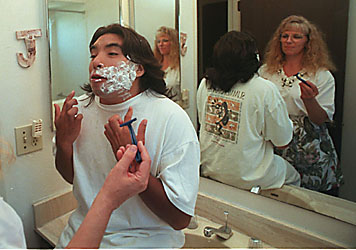

Theresa Kellerman shaves the face of her son John, who lacks the concentration to shave himself.

![]() Kellerman worries about what will happen to John after he graduates. She worries even more about what will happen to John when she's gone.

Kellerman worries about what will happen to John after he graduates. She worries even more about what will happen to John when she's gone.

![]() "I look at John, and I think, 'He wants to be independent and he can't be.

"I look at John, and I think, 'He wants to be independent and he can't be.

![]() "He knows if his birth mother didn't drink, he wouldn't have these problems. It's very depressing. When I think about it or talk about it, it causes a lot of emotional pain.

"He knows if his birth mother didn't drink, he wouldn't have these problems. It's very depressing. When I think about it or talk about it, it causes a lot of emotional pain.

![]() "I fear for his future. The services are not in place for him to be happy and healthy, and he's just one kid. What about all the others? It's simply overwhelming."

"I fear for his future. The services are not in place for him to be happy and healthy, and he's just one kid. What about all the others? It's simply overwhelming."

![]() When Kellerman adopted "Johnny" 20 years ago, information about FAS was just coming out. But Kellerman didn't need scientific studies to know the baby was a handful.

When Kellerman adopted "Johnny" 20 years ago, information about FAS was just coming out. But Kellerman didn't need scientific studies to know the baby was a handful.

![]() Johnny could handle no stimulation. He cried pitifully and slept fitfully. "He cried and cried and cried, and nothing soothed him," Kellerman recalled.

Johnny could handle no stimulation. He cried pitifully and slept fitfully. "He cried and cried and cried, and nothing soothed him," Kellerman recalled.

![]() Johnny was overwhelmed by sound and light and couldn't concentrate on drinking the baby formula Kellerman offered.

Johnny was overwhelmed by sound and light and couldn't concentrate on drinking the baby formula Kellerman offered.

![]() She desperately wanted to cuddle her baby boy and offer the love he was missing from his birth mother.

She desperately wanted to cuddle her baby boy and offer the love he was missing from his birth mother.

![]() But John didn't want to be held. The more Kellerman tried to sooth him, the more upset he grew.

But John didn't want to be held. The more Kellerman tried to sooth him, the more upset he grew.

![]() So Kellerman learned to love Johnny from a distance.

So Kellerman learned to love Johnny from a distance.

![]() As a toddler, Johnny was charming and loving. It was then that Kellerman first told him about FAS.

As a toddler, Johnny was charming and loving. It was then that Kellerman first told him about FAS.

![]() "He'd sit on my lap as a baby, and I'd talk about his adoption and his syndrome," she said. "There's been nothing hidden."

"He'd sit on my lap as a baby, and I'd talk about his adoption and his syndrome," she said. "There's been nothing hidden."

![]() As John grew, so did his problems.

As John grew, so did his problems.

![]() His hyperactivity became more severe. He grew angry at his birth mother at around 10.

His hyperactivity became more severe. He grew angry at his birth mother at around 10.

![]() "I can remember him sitting at the kitchen counter, saying, 'Do you mean if my birth mother didn't drink, I wouldn't have these problems?'" Kellerman recalled. "I said, 'That's right,' and he got so angry."

"I can remember him sitting at the kitchen counter, saying, 'Do you mean if my birth mother didn't drink, I wouldn't have these problems?'" Kellerman recalled. "I said, 'That's right,' and he got so angry."

![]() Another problem that plagues John is the physical contact he craves. He has always loved to give hugs. As he grew older, the hugs became more sexual, and Kellerman worries John's hugs will get him in serious trouble. Her biggest fear is that he could be arrested for inappropriate sexual behavior.

Another problem that plagues John is the physical contact he craves. He has always loved to give hugs. As he grew older, the hugs became more sexual, and Kellerman worries John's hugs will get him in serious trouble. Her biggest fear is that he could be arrested for inappropriate sexual behavior.

![]() "We have to have a concrete rule: No hugs," Kellerman said. "He can have as many hugs from me as he wants. He has plenty of people providing affection."

"We have to have a concrete rule: No hugs," Kellerman said. "He can have as many hugs from me as he wants. He has plenty of people providing affection."

![]() Earlier this month, John started taking Paxil, an antidepressant Kellerman hopes will control his sexual urges.

Earlier this month, John started taking Paxil, an antidepressant Kellerman hopes will control his sexual urges.

![]() John knows he's not supposed to hug women he doesn't know. But when Kellerman isn't looking, he tries to make physical contact.

John knows he's not supposed to hug women he doesn't know. But when Kellerman isn't looking, he tries to make physical contact.

![]() John's hugs have gotten him in trouble at school and in the community. Afraid that he would be arrested, Kellerman drummed into John's head that he could be locked up if he were't careful.

John's hugs have gotten him in trouble at school and in the community. Afraid that he would be arrested, Kellerman drummed into John's head that he could be locked up if he were't careful.

![]() "He became so afraid of that, he told me maybe it would be better to be dead than be in jail," Kellerman said.

"He became so afraid of that, he told me maybe it would be better to be dead than be in jail," Kellerman said.

![]() Kellerman continually reassures John that she'll be his conscience.

Kellerman continually reassures John that she'll be his conscience.

![]() "I told him he'll never be in jail, as long as I am with him," Kellerman said. "I'll provide him with 24-hour supervision if that's what it takes."

"I told him he'll never be in jail, as long as I am with him," Kellerman said. "I'll provide him with 24-hour supervision if that's what it takes."

![]() For John to succeed, he must live and work in a highly structured world, Kellerman said.

For John to succeed, he must live and work in a highly structured world, Kellerman said.

![]() She found herself nagging John about what he needed to do.

She found herself nagging John about what he needed to do.

![]() So for the past couple of years, Kellerman has kept a detailed schedule on the kitchen wall.

So for the past couple of years, Kellerman has kept a detailed schedule on the kitchen wall.

![]() "He's learning to be responsible for himself. He asks me, 'Mom, what am I supposed to be doing?' And I'll say, 'Check your chart.'"

"He's learning to be responsible for himself. He asks me, 'Mom, what am I supposed to be doing?' And I'll say, 'Check your chart.'"

![]() It all starts with his alarm going off at 6:30. Shower 6:40. Shampoo 6:50. Put on deodorant at 7, take Ritalin and make the bed.

It all starts with his alarm going off at 6:30. Shower 6:40. Shampoo 6:50. Put on deodorant at 7, take Ritalin and make the bed.

Feed the dog at 7:15, eat cereal, brush teeth and get out the door for the school bus. And so on and so on, throughout the day, all day, every day.

![]() "His neurological process is so messed up, he'll never be able to remember all of this on his own." Kellerman said, looking at he chart. "We've got making the bed in the morning down pat. But he still can't remember to use his deodorant."

"His neurological process is so messed up, he'll never be able to remember all of this on his own." Kellerman said, looking at he chart. "We've got making the bed in the morning down pat. But he still can't remember to use his deodorant."

![]() Parenting John, as difficult as it is, is the easy part, Kellerman says.

Parenting John, as difficult as it is, is the easy part, Kellerman says.

![]() "The hardest part is dealing with teachers and professionals," she said. "You have to really know all about FAS and what it is to make a positive impact."

"The hardest part is dealing with teachers and professionals," she said. "You have to really know all about FAS and what it is to make a positive impact."

![]() Kellerman frequently meets with John's teachers, counselors and other professionals. She's in his corner every minute.

Kellerman frequently meets with John's teachers, counselors and other professionals. She's in his corner every minute.